In this ongoing series, we ask SF/F authors to describe a specialty in their lives that has nothing (or very little) to do with writing. Join us as we discover what draws authors to their various hobbies, how they fit into their daily lives, and how and they inform the author’s literary identity!

One of the final panels of the Bayeux tapestry depicts a man scaling the roof of a large church clutching a weathervane. The church may be the first incarnation of Westminster Abbey in London, and the man shown is someone once called a “steeple climber.” Such people worked to build, clean, and maintain tall structures; as their name suggests, the original work in medieval Britain focused largely on the spires and towers of high civic and ecclesiastical buildings. These were the guys who used systems of ladders and ropes to scale those otherwise inaccessible structures to fix up what the regular masons wouldn’t go near. While they may have been employed for long-term work during the construction of a major abbey like Westminster, their work was largely itinerant, and they travelled from town to town repairing church towers and the like, often combining the labor with a sideshow display of aerial acrobatics and feats of daring. It was a dangerous profession, as can easily be imagined when you consider working on a steeple like Saint Walburge, located in my hometown of Preston, which is a dizzying 309 feet high.

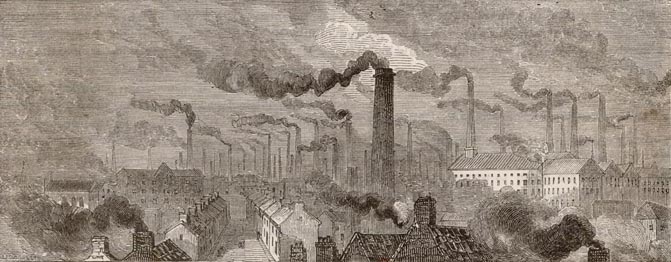

Records surviving from the 1760s depict the tools of the steeple-climber in terms that remain unchanged for the next two centuries: the bosun’s chair (a short plank or swath of heavy fabric on which someone might sit suspended), iron “dogs” (hooked spikes that were driven into masonry to anchor ropes or ladders), and staging scaffold. But church spires and clock towers alone wouldn’t provide much employment for steeplejacks. In the nineteenth century their work shifted to the more mundane, less elegant, and far more numerous structures which were sprouting all over England’s northwest: chimneys. The Industrial Revolution brought mills and factories and increasing mechanization, all steam-driven and fuelled by coal and coke, and their chimneys needed constant maintenance. The steeple climber was suddenly in regular demand, and some time around the 1860s they became known by a more-familiar title: steeplejack.

I grew up in Lancashire, the work horse of Britain’s industrial revolution in the nineteenth century, and it was impossible not to know what a steeplejack was, though they had already become rare curiosities. The most famous twentieth century steeplejack, Fred Dibnah, said that from a particular vantage point in his hometown of Bolton—just down the road from my own Preston—he could, as a kid, count 200 towering chimneys over that cluttered industrial landscape. Lancashire was the heart of the British textile industry, and a good deal of those chimneys were attached to spinning and weaving sheds, though that industry had been steadily dying since before World War I. By the time I was born in 1964, many of those chimneys had gone, and those that remained tended to be disused, maintained only to stop them posing a risk to people and property below, and—eventually—subjected to the steeplejack’s special brand of controlled demolition. As the chimneys vanished, so did the steeplejacks, and when the local news featured Dibnah in 1978 during his work on Bolton’s town hall clock tower, he caught the attention of the BBC, who based an award-winning documentary on him the following year. Part of Dibnah’s charm—in addition to his broad Lancashire accent and cheery fearlessness when hundreds of feet aloft—were his old-fashioned methods. He was a throwback, a remnant of a former age and for all its delight in him and his work, the documentary was ultimately elegiac.

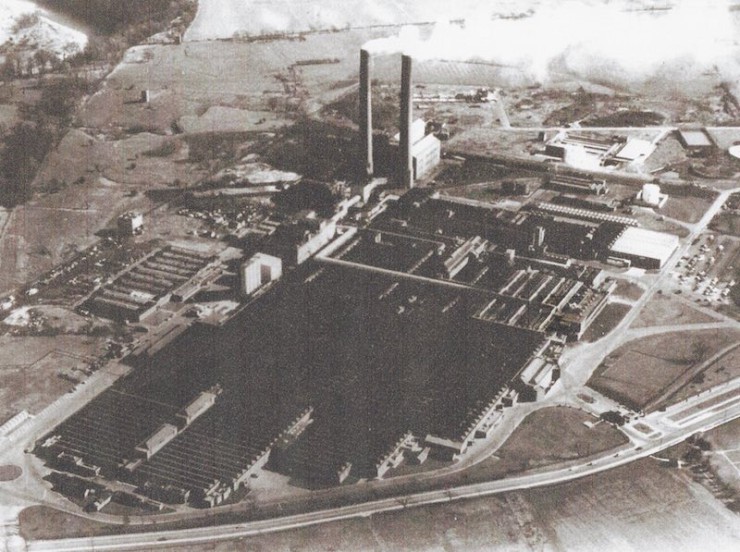

I attended a high school in the shadow of Courtauld’s textile factory at Red Scar, a factory boasting a pair of massive cooling towers and two great cannon-like chimneys which stood an astonishing 385 feet tall. They were a landmark for miles around, the first sign on family road trips that you were nearly home, and though they were in many ways an eyesore, I find myself looking for them whenever I returned from my travels. They were demolished in 1983, and not in the old fashioned way Fred Dibnah would have done it. Dibnah would have carved a hole in the bricks at the base of the chimney, supporting the whole with timber struts, then setting a fire which would eventually bring the chimney crashing down—if he had done his job properly and accurately calculated the timing and wind speed—along a precise line, causing minimal damage to surrounding structures. But the Courtauld’s chimney demolition was the end of an era, one which wiped that area of Preston clean of its industrial past, so it was perhaps fitting that even the method used—explosive implosion—should turn its back on traditional methods.

Indeed, the very profession of steeplejacking has almost entirely vanished now. Health and safety regulations allow no place for the Fred Dibnahs of the old world, sitting cheerfully on a plank suspended over a couple of hundred feet of nothing, even if the great factory smokestacks were still there to demand the work. I’m under no illusions about the allure of the Victorian past, built as it was on filthy and brutal working conditions, on empire, and on the exploitation of slavery: It was years before I realized that what we knew as the Great Cotton Famine in Lancashire was known in the United States as the American Civil War! Still, I can’t help but feel a pang of loss for the extraordinary structures which once defined the region I grew up in, and whose loss signaled decades of hardship and high unemployment.

I live in Charlotte, North Carolina, now. Though the city has had its share of industrial manufacturing, it was always primarily a trade and finance center, so there’s precious little of the kind of grand Victorian architecture that you still see dotted around northwest England. But if you take the I-277 ring road round the east side of the city heading north and you look directly right as you pass the cement works on the freight line, you can see two brick chimneys, one of which is lit up at night. They are square-sided, more like one of Preston’s last remaining Victorian chimneys attached to the Horrocks textile mill, and nothing like so tall as the Courtaulds stacks which so overshadowed my childhood. But they are good, solid, purposeful chimneys, and the one furthest from the road is distinctive because there is a bush growing out of the very top, an untended weed, left to flourish in the absence of an attentive steeplejack who would have kept the mortar clear and the brickwork pointed. Spotting that defiant shrub on my drive to work is an evocative reminder of the people whose hands once built it and whose labor to maintain it took nerve and skill—work in which, I suspect, they took great pride.

A.J. Hartley is the bestselling author of a dozen novels including Sekret Machines: Chasing Shadows (co-authored with Tom DeLonge) and the YA fantasy adventure Steeplejack from Tor Teen. As Andrew James Hartley, he is also UNC Charlotte’s Robinson Distinguished Professor of Shakespeare, specializing in performance theory and practice, and is the author of various scholarly books and articles from the world’s best academic publishers including Palgrave and Cambridge University Press. He is an honorary fellow of the University of Central Lancashire, UK.

A.J. Hartley is the bestselling author of a dozen novels including Sekret Machines: Chasing Shadows (co-authored with Tom DeLonge) and the YA fantasy adventure Steeplejack from Tor Teen. As Andrew James Hartley, he is also UNC Charlotte’s Robinson Distinguished Professor of Shakespeare, specializing in performance theory and practice, and is the author of various scholarly books and articles from the world’s best academic publishers including Palgrave and Cambridge University Press. He is an honorary fellow of the University of Central Lancashire, UK.